- Home

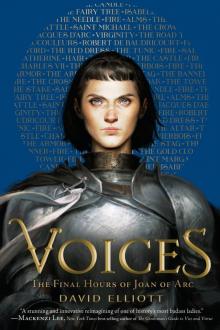

- David Elliott

Voices Page 5

Voices Read online

Page 5

accompanied me to Poitiers,

where the learnèd scholars of the

day convened to test and question

me. Their knowledge of theology

would tell the king with certainty

if my suit was false or true.

For three long weeks they put me through

a ceaseless and a silly trial.

Question after question, and all

the while Orléans was bleeding.

The proceedings of the trial

even called for rough and intimate

examinations to make sure

I was intact. I endured this

humiliation. If not, they

would have said that I had made a

pact with Hell. I know them well, these

men, always looking for the worst.

The world is cursed with them, but my

king needed their assurance, their

trust, their word that I was who I

said I was, and so with my

saints and my virginity, I

submitted and endured. I did

not let them see that I was

disquieted and bored. Instead, I sent

an urgent message to Fierbois,

asking for another sword, a

blade that I thought suited me very,

very well—a hero’s sword from

long ago, the sword of Charles Martel.

SENT to seek for a sword which was in the Church of Sainte Catherine de Fierbois, behind the altar; it was found there at once; the sword was in the ground, and rusty; upon it were five crosses; I knew by my Voices where it was. . . . I wrote to the Priests of the place, that it might please them to let me have this sword, and they sent it to me. It was under the earth, not very deeply buried, behind the altar, so it seemed to me.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

The Sword at Fierbois

Joan

I know that swords are necessary

things: Without them there can be no

war. But what they were invented

for is not a skill that I revere.

No matter how it may appear,

though I have ridden into fierce

and violent campaigns and have

suffered stinging losses and enjoyed

exalted gains that come with

any great hostility, neither

in the revenge of defeat nor

the madness of victory have

I used a sword to take another’s

life. I’ve never made a widow

of an Englishman’s wife, never

caused a soldier’s blood to flow and

spill. I was born to lead and to

inspire, not to maim and kill.

* * *

These illusions and distracting

memories help to ease the pain

and fear of the burning present.

The sun, which I used to love, I

now lament, for he is now my

fiercest adversary. With every

second he climbs higher and brings

me closer to his functionary:

fire.

Fire

I soar I soar I soar my darling

I soar I soar I soar

I will I will I will my darling

I will I will I will

I thrill I thrill I thrill my darling

I thrill I thrill I thrill

I burn I burn I burn my darling

I burn I burn I burn

I arn y I ea y rling

yea I a rn

Joan

Time was squandered at Poitiers.

As day followed day followed day

followed day, the king was anguished,

in despair, as despondent as

a frightened hare caught in an English

trap. He was young and had no guide,

no recourse, no map to tell him

what to do. Each hour that passed brought

him closer to the day when Orléans

would capitulate. He was anxious,

moody, desperate. But finally

the decision came. The priests could

find in me “no blame.” They assured

the king they could discern no harm.

And though it maddened and alarmed

his aides, he paid to have me fitted

with the hard accouterments

of war.

HE King gave her a complete suit of armor and an entire military household.

* * *

Louis de Contes

Trial of Nullification

The Armor

I did my job;

I did my very best

to shield her from the pain of injury. But it was all in vain. She

would not rest until she had been captured and oppressed.

She’d always been her own worst enemy. But I did

my job. I did! My very best plate against her legs

and back and chest, my chain protecting neck and

wrist and knee. But it was all in vain. She would not

rest while Henry’s English army still possessed

a single hectare of French land. Still, don’t you

see, I did my job? I did my very best to slow

her down, but she could not be suppressed

by the weight of steel or by rationality.

My work was all in vain; she would not rest.

I did my job, but she? She was possessed by

some internal fire, consumed, obsessed. I did my job

and did my very best, yet my ambition was in vain.

She would not rest.

Joan

Orléans was to be my test.

If I could lift the siege and

arrest the progress of the English

there, bait and defeat them the way

the hunter does a savage bear,

the king would know that I was not

a charlatan or fraud, that in

truth, I had been sent by God to

save France from its English enemies,

to chase them from our homeland and

to bring Henry to his knees. Orléans

had been surrounded for eight long

and trying months. Charles had tried

more than once to liberate the

town, but each time he’d been defeated.

His meager resources now depleted,

his enemies grew stronger, his

most accomplished knights no longer

able to break the might of the

filthy English scourge, or purge them

from their fortified positions.

I sent the English captains a

warning with grave admonitions

that unless they withdrew before

another morning’s dew had fallen

on French soil, they would find themselves

in the turmoil of defeat. They

laughed and called me whore. I was just

a girl. No more than sixteen with

no experience of war and

no military training. They

must have thought me very entertaining.

That was their mistake. At daybreak

I led my army into Orléans,

unopposed and undetected.

The way the town greeted me, cheering

and calling for the Maid, reflected

the long and bloody price they’d paid,

their anguished months of suffering, their

awful desperation. I told

them to take heart. Their liberation

had arrived. They had survived in

order to be saved. How they wept

and laughed and cheered and waved while their

great relief and happiness drifted

on the air! And how my spirits

lifted with their steadfast faith in me.

Where are they now, those shining

hours,

those brilliant days of victory?

Victory

I am a pail

that will not hold.

I am a fire

that soon burns cold,

the first half

of a story.

* * *

I am a bird

that won’t be held,

a godhead’s name

that’s been misspelled.

Both truth

and allegory.

* * *

A paramour

who will not wake,

a round of bread

that will not bake.

A trickster’s repertory.

* * *

I am a war cry,

bold and brash.

I am kindling.

I am ash,

an evanescent glory.

Joan

On the first morning of the fight

as light fell just after dawn, an

English arrow struck deep between

my neck and shoulder. The sight of

my own blood sickened me, but it

also made me bolder. Though I

was bleeding badly, I did not

leave the field of battle but

continued leading my brave men,

shouting we were not chattel of

the English but the liberators

of all France. “Advance!” I cried out

through the pain.

“Advance!”

* * *

“Advance!”

* * *

“Advance!”

HE twenty-seventh of May, very early in the morning, we began the attack on the Boulevard of the bridge. Jeanne was there wounded by an arrow which penetrated half-afoot between the neck and the shoulder; but she continued nonetheless to fight, taking no remedy for her wound.

* * *

Jean, bastard of Orléans, count of Dunois

Trial of Nullification

The Arrow

It

makes

no sense.

She should

have died. I saw

my mark and I

went deep. My gift

ignored. My joy denied.

It makes no sense. She

should have died. The pain she

seemed to brush aside: She was a

vow I could not keep. It makes no

sense. She should have died. I saw

my mark and I

went deep.

Joan

Then as now I was guided by

my voices. All the choices I

made in the bloody days that followed

came from my hallowed saints, including

the constraints I put on my men

when the English gave up and departed.

Some thought me weak or tenderhearted,

for I had spoken to Henry’s

captains, promising their safe retreat.

* * *

The English defeat had shown the

king that I was his protector

and salvation. My success was

irrefutable, a clear and

certain confirmation that faith

in me would lead him to triumphant

victory. I did not want to

stain this gift with needless butchery.

At the siege of Orléans, I

finished what I started. My

strategy was simple: We would

fight until we won. And in eight

short days, I, Joan, a peasant girl,

did what in eight long and crimson

months no clever man had done.

T was said that Jeanne was as expert as possible in the art of ordering an army in battle, and that even a captain bred and instructed in war could not have shown more skill; at this the captains marveled exceedingly.

* * *

Maître Aignan Viole

Trial of Nullification

Joan

We went on to be victorious

in other towns the English held.

Word spread; my forces swelled. Farmers

joined my army with nothing more

than spikes; some had only pitchforks,

some only wooden pikes. They asserted

as much chivalry as any

royal knight. In all, I had six

thousand men, each eager to be

led by me. We took Jargeau,

Meung-sur-Loire, and long-bridged

Beaugency.

EANNE assembled an army between Troyes and Auxerre, and found large numbers there, for everyone followed her.

* * *

Gobert Thibaut, squire to the king of France

Trial of Nullification

The Pitchfork

Joan

I loved the military life,

though it was often rife with

peril, the men I fought with nearly

feral when their blood was up. I

shared their food. I shared their cup.

When they slept depleted on the

unforgiving ground, I lay there

too, surrounded by the sound of

soldiers in their dreams. The moan, the

muttered word, the restlessness, the

sigh, were as comforting to me

as any lullaby and proof I

was not mending seams or tilling

rocky land. Instead I was in

firm command of brave and fighting

men. The war is not yet over,

but I will not see those thrilling

days or know that happiness again.

Fire

I roar I roar I roar my darling

I roar I roar I roar

I soar I soar I soar my darling

I soar I soar I soar

I will I will I will my darling

I will I will I will

I thrill I thrill I thrill my darling

I thrill I thrill I thrill

I bu b rn I n my ling

rn n I bu

I arn y I ea y rling

yea I a rn

Joan

My saints were always there beside

me, to counsel, cheer, console, and

guide me. And they helped in other

ways: We were marching in the summer

haze toward the commune of Patay,

where English captains, bold and sly,

had set a snare, their men concealed

among the trees. With ready bows

and hungry swords they waited to

attack. But before this black plan

could be enacted and embraced,

a stag raced from a clearing.

Appearing from nowhere, large and wild,

he charged into the woods where the

Englishmen were hiding. I was,

as always, riding at the head

of my troops and saw frightened groups

of Henry’s soldiers scatter, the

clatter of their swords as good a

warning as an alarm. They knew

the fatal harm the stag’s sharp

antlers could impose. A clever

ambush was thus exposed. Four thousand

English died that day, the awful

price they had to pay for their flagrant

treachery, but their agonizing

loss was our tremendous victory.

Who but my saints would send that stag,

as sure a signal as a flag

alerting me to jeopardy?

I know this as surely as I

know my father’s cattle graze

unshod: The stag was sent to me

by Heaven; the stag was sent to

me by God.

THINK that Jeanne was sent by God, and that her behavior in war was a fact divine rather than human. Many reasons make me think so.

* * *

Jean, bastard of Orléans, count of Dunois

Trial of Nullification

> The Stag

She says it was Heaven. I say it was Hell

that morning in the woodland glade

when unannounced and unafraid

I charged those soldiers. Who can tell?

* * *

Four thousand men died in that dell.

I can’t forget the serenade

of dying screams, the acrid smell

of bitter blood beneath the blade

* * *

on the soft ground where they fell.

They’d gone to Mass, confessed and prayed,

and still transformed from man to shade,

the clash of swords their clanging knell.

She says it was Heaven. I say it was Hell.

Joan

After victory at Orléans

and the Battle of Patay, the

king had confidence that I, and

I alone, could rescue France. My

voices said to take the king to

Reims, where he would at last be

consecrated by the holy

oil with which French kings must be

anointed. The men around him

were pointed in their discouragement

of this dangerous endeavor,

for we would ride through land that

Henry’s soldiers held. They were clever,

these advisors, warning that the

English would never be expelled

if Charles were caught and in their

hands. But even as they spoke, Henry’s

men were thriving on French lands,

growing fatter every day. In

this matter, I told Charles he

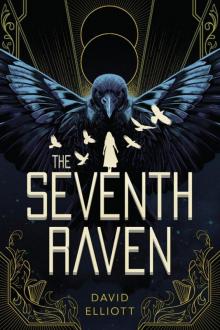

The Seventh Raven

The Seventh Raven Voices

Voices Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie

Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie Fluke

Fluke