- Home

- David Elliott

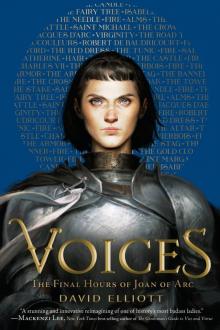

Voices

Voices Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Before You Read

Map of Holy Roman Empire

Prologue

The Candle

Joan

Fire

Joan

The Fairy Tree

Joan

Isabelle

Joan

The Needle

Joan

Silence

Joan

Fire

Alms

Joan

The Cattle

Joan

Saint Michael

Joan

The Crown

Joan

Jacques D’Arc

Joan

Virginity

Joan

The Road to Vaucouleurs

Joan

Robert De Baudricourt

Joan

Fire

Joan

The Sword

Joan

The Red Dress

Joan

The Tunic

Joan

Joan

Fire

Saint Catherine

Joan

Lust

Joan

Her Hair

Joan

The Altar at Sainte Catherine De Fierbois

Joan

The Castle at Chinon

Joan

Charles VII

Joan

The Sword at Fierbois

Joan

Fire

Joan

The Armor

Joan

Victory

Joan

The Arrow

Joan

Joan

The Pitchfork

Joan

Fire

Joan

The Stag

Joan

The Warhorse

Joan

The Banner

Joan

Fire

Joan

Charles VII

Joan

The Crossbow

Joan

The Gold Cloak

Joan

The Tower

Joan

Saint Margaret

Joan

The Stake

Joan

Bishop Pierre Cauchon

Joan

Fire

Joan

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Sample Chapters from BULL

Buy the Book

More Books from HMH Teen

About the Author

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Copyright © 2019 by David Elliott

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

All trial excerpts from “Saint Joan of Arc’s Trials,” Saint Joan of Arc Center (stjoan-center.com), New Mexico, founded by Virginia Frohlick.

hmhbooks.com

Cover illustration © 2019 by Charlie Bowater

Cover design by Sharismar Rodriguez

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Names: Elliott, David, 1947– author. | Title: Voices / by David Elliott.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2019]

Audience: Grades 9–12. | Audience: Ages 14 and up.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018025855 | ISBN 9781328987594 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Joan, of Arc, Saint, 1412–1431—Juvenile literature. Christian women saints—France—Biography—Juvenile literature. Christian saints—France—Biography—Juvenile literature. Women soldiers—France—Biography—Juvenile literature. Soldiers—France—Biography—Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC DC103.5 .E45 2019

DDC 944/.026092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018025855

eISBN 978-0-358-04915-9

v1.0319

To Kate O’Sullivan, editor extraordinaire and Kelly Sonnack, agent nonpareil—women warriors in their own right. How lucky I am!

Before You Read

Much of what we know about Joan of Arc comes from the transcripts of her two trials. The first, the Trial of Condemnation, convened in 1431, found Joan guilty of “relapsed heresy” and famously burned her at the stake. The second, the Trial of Nullification, held some twenty-four years after her death, effectively revoked the findings of the first. In both cases, the politics of the Middle Ages guaranteed their outcomes before they started. It is in the Trial of Condemnation that we hear Joan in her own voice answering the many questions her accusers put to her. In the Trial of Nullification, her relatives, childhood friends, and comrades-in-arms bear witness to the girl they knew. Throughout Voices, you will find direct quotes from these trials.

Oh, one more thing: Because the book is written in rhymed and metered verse, it’s important to get the pronunciation of the French names and places right. Here’s a quick pronunciation guide to help you out.

DOMRÉMY: dom-ray-MI (very much like the song)

TROYES: twah (rhymes more or less with “law”)

CHINON: she-NOHN

VAUCOULEURS: voh-koo-LEUHR

ORLÉANS: OR-lee-OHN (three, not two, syllables)

PATAY: puh-TYE

REIMS: rahnce (not reems)

ROUEN: ROO-uhn (kind of like the English word “ruin”)

Prologue

ROM her earliest years till her departure, Jeannette [Joan] the Maid was a good girl, chaste, simple, modest, never blaspheming God nor the Saints, fearing God. . . . Often she went with her sister and others to the Church and Hermitage of Bermont.

* * *

Perrin Le Drapier, churchwarden and

bell-ringer of the Parish Church

Trial of Nullification

The Candle

I

recall

it as if it were

yesterday. She was

so lovely and young. In

her hand I darted and flick-

ered away, an ardent lover’s ad-

venturing tongue. I had never known

such yearning, exciting and risky and

cruel. As we walked to the church, I was

burning; she was my darling, my future,

my fuel. I wanted to set her afire right then.

But she was so pure, so chaste; her innocence

only increased my desire. Still, I know the

dangers of haste. So I watched and I studied

and waited, and I saw that her young blood

ran hot. She had no idea we were fated. I

could name what she craved; she could

not. Then in her eye, I caught my

reflection. In her eye, I saw my-

self shine, and I saw the heat

rise on her virgin’s com-

plexion. That’s when

I knew: She was

mine.

Joan

I’ve heard it said that when we die

the soul discards its useless shell,

and our life will flash before our

eyes. Is this a gift from Heaven?

Or a jinx from deepest Hell? Only

the dying know, but what the dying

know the dying do not tell. What

more the dying know it seems I

am about to learn. For when the

sun is at its highest, a lusting torch

will touch the pyre. The flames will rise.

And I will burn. But I have always

been afire.

With youth. With faith. With

truth. And with desire. My name is

Joan, but I am called the Maid. My

hands are bound behind me. The fire

beneath me laid.

Fire

I yearn I yearn I yearn my darling

I yearn I yearn I yearn

Joan

Every life is its own story—

not without a share of glory,

and not without a share of grief.

I lived like a hero at seventeen.

At nineteen, I die like a thief.

* * *

I’ll begin with my family:

a father, a mother, uncles

and aunts, one sister, two brothers,

all born in Lorraine in the

Duchy of Bar. Domrémy is

our village. It’s north of the Loire,

the chevron-shaped river that cuts

across France. My parents were peasants,

caught up in the dance that all the

oppressed must step to and master:

work harder, jump higher, bow lower,

run faster. The feel of the earth

beneath my bare feet, the sun on

my face, the smell of the wheat as

it breaks through the soil, the curve of

the sprout as it bends and uncoils,

the song of the beetle, the hum

of the bees. I was comforted

by these, but they would not have

satisfied me, for something other

occupied me. To take the path

that I have taken, I have abandoned

and forsaken everything I

once held dear, and that, in part, has

brought me here, to die alone bound

to this stake. Each decision that

we make comes with a hidden price.

We’re never told what it is we

may be asked to sacrifice.

* * *

A shape begins to form itself

in the air in front of me. Trunk . . .

and roots . . . an ancient tree, its limbs

so low they touch the earth. I know

it now. Around its girth we village

children sang and danced. The tree was

thought to be entranced; our elders

said beneath its shade a band of

brownies lived and played. I wonder

if they live there still, or have, like

me, they been betrayed?

OT far from Domrémy there is a tree that they called “The Ladies Tree”—others call it “The Fairies Tree.” . . . Often I have heard the old folk—they are not of my lineage—say that the fairies haunt this tree. . . . I have seen the young girls putting garlands on the branches of this tree, and I myself have sometimes put them there with my companions.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

The Fairy Tree

I sing the mournful carol of five hundred passing

years. Nurtured by the howling wind and the

music of the spheres, I have retained the record

of every heart that ever broke, every wound that

ever bled. I remember single drops of rain, every

day of golden light, the sorrow of the cuckoo’s

crimes, the lightning strikes, the trill of every

lark. And I have stored the memory of these

consecrated things in the scarred and winding

surface of my incandescent bark. Etched there,

too? The face of every child who cherished me,

who sang my name—the Fairy Tree. They came

to celebrate the sprites who lived beneath my

canopy, for I was the fairies’ chosen, their syl-

van hideaway. The brindled cows looked on at

human folly when the fairies were charged and

banished by the village priest. The children, too,

have vanished, undone by years, and worms, and

melancholy. Yes, all my children I recall, but it

is Joan who of them all stands apart in the con-

centric circles of my ringèd memory. She hid it

well—the burning coal that was her heart. But

a tree is ever watchful in the presence of a flame,

and I saw in her a smoldering, a spark, a heat

well beyond extinguishing. I feel it even now, that

heat. It blazes just the same. Elements not rec-

onciled, as disparate as day and night, sparked

an unrelenting friction destined to ignite some-

thing hybrid, new, and wild. It was a heavy fate

for such a child, so small and young. And yet

among the girls she was a favorite, their affec-

tion for her zealous. But the boys were threat-

ened. Rough. Rugged. Strong. Athletic. They

did not know that they were jealous. I see now it

was prophetic, the rancor hidden in their hearts.

But rancor is a stubborn guest; once lodged, it

won’t depart. The village priest abides here still,

or his likely twin, still finding evil in every joy,

still scolding the girls, still eyeing the boys, still

holding up pleasure and calling it sin. As for the

girl, for Joan, she remains a mystery. Who can

say why some arrive and then depart forgotten

while others fashion history?

Joan

The illusion of the tree is

fading. I see my mother now,

separating good peas from the

bad. Clad in homespun, she has just

come from the stable. But the light

is dim. I am unable to

see her careworn face, and so I

trace the swift movement of her hands—

the blunt fingers callused and bent,

the rough knuckles swollen and cracked.

But those earthly imperfections

could never detract from the inborn

grace with which they move, the rough

gestures that I know and love. When

I left Domrémy to join the

world of soldiery and men, how

could I have known that I would

never feel my mother’s touch or

see her hands again?

EANNE [Joan] was born at Domrémy and was baptized at the Parish Church of Saint Remy, in that place. Her father was named Jacques d’Arc, her mother Isabelle—both laborers living together at Domrémy. They were, as I saw and knew, good and faithful Catholics, laborers of good repute and honest life.

* * *

Jean Morel, laborer

Trial of Nullification

Isabelle

What is a woman?

Her brothers’ sister, her father’s daughter,

Her husband’s wife, her children’s mother.

Milk the cow, churn the butter, slop the pig, spin

the flax, nurse the sick, boil the soup, knead

the dough, bake the bread, mind

* * *

the children, mind the sheep, mind

your manners. These are what a woman

learns to become a wife, skills all women need,

and skills I have passed on to Joan, my daughter.

I taught her to churn, to bake, to plant, to spin.

Wasn’t that my duty as her mother?

* * *

I learned them as a girl from my own mother,

who learned them as a girl from hers. Mind

you, there are days my head spins

like the stars over me, but a woman

is not her own master. She is the daughter

of Urgency, a servant to Need.

* * *

From the start, Joan didn’t need

or want what other girls needed, her mother,

for example. It hurts to have a daughter

/>

who so clearly knows her own mind.

Such qualities are dangerous in a woman.

She was a contradiction, able to sew and spin

* * *

better than any girl in the village, married or spin-

ster. And what she could do with a need-

le, well, there is still not a woman

who could match her. But a mother?

A farmer’s wife? No. In my mind

she was more son than daughter,

* * *

keeping her silence, a daughter

who would churn, cook, sew, spin

without complaint. Yet her mind

was elsewhere, settled on another need,

a need she could not share with her mother

or any other woman.

* * *

Mothers should understand what their daughters

need. But Joan and I were never of one mind.

Spin! I begged her. Spin like a woman!

Joan

To spin like a woman was not

my fate. I had other talents,

concealed but innate, that even

now are hard for me to comprehend.

I only know that to wash and

mend my brothers’ tunics aroused

in me an aching discontent.

This low unhappiness was the

advent of everything that followed. But

I swallowed my pride, nodded, smiled,

and swore that I would best every

female task my mother assigned. All

that to which I felt more naturally

inclined I vowed to put aside.

But the harder I tried, the more

it pressed. I was beset by my

own nature, possessed by a ruthless

and persistent urge, as if there

were another me waiting to

emerge from all that was constraining.

But about this, I said nothing

and continued with my training.

N your youth, did you learn any trade?”

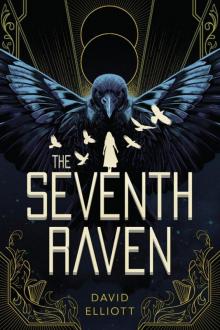

The Seventh Raven

The Seventh Raven Voices

Voices Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie

Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie Fluke

Fluke