- Home

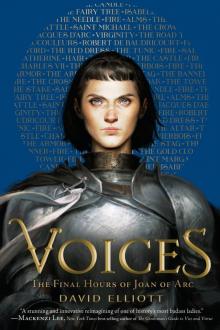

- David Elliott

Voices Page 4

Voices Read online

Page 4

the simple dress they proffered and

my own hypocrisy. I took

off the shift and donned the clothes more

natural to me. I knew then

I would face my death unafraid

and proud. If that meant that my

tunic would also be my shroud,

then I would enter Paradise

a bright and shining jewel, not an

abomination, but the way

that God has made me, His singular

creation.

AS it God prescribed to you the dress of a man?”

Joan: “I did not take it by the advice of any man in the world. I did not take this dress or do anything but by the command of Our Lord and of the Angels.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

Joan

How strange it is not to be confined

in my tower cell—where they have

imprisoned me well over a

long year—to feel the spring sun on

my skin! What is it that these angry

men so fear that they treat me like

a criminal? They say it was

a sin to stand up for Charles

and for France. Yes, I carried sword

and shield and lance onto the teeming

battlefield, but I have never

been untruthful or concealed my

true intentions. They say I am

a sorceress, but that is only

an invention to protect them

from their own dark villainy, their

unmanly apprehensions

and disguised anxieties. They

are angry that I would not give

them satisfaction by saying

I was guilty or signing a

retraction. But I will not let

them harvest the bitter seeds of

fear they’ve sown. I am not afraid

because I am not alone. Saint

Margaret and Saint Catherine will

never desert me. They will keep their

promise: No one can hurt me.

Fire

I will I will I will my darling

I will I will I will

I thrill I thrill I thrill my darling

I thrill I thrill I thrill

I burn I burn I burn my darling

I burn I burn I burn

I yearn I yearn I yearn my darling

yea I a rn

Saint Catherine

Barbers and bakers approach me in prayer,

and those who know their philosophy,

and lawyers and young girls with long, unbound hair

and wheelwrights and scribes, too, supplicate me,

and millers and preachers and potters feel free

to beg and beseech me. I do what I can,

but I am not now what I once used to be.

Saints are only human.

* * *

I would also like to make you aware

I converted to true Christianity

hundreds of pagans. I once had a flare

for debate, religion, theology,

was renowned for the skill of my oratory.

Oh, yes, I was quite the sesquipedalian.

But all that is gone. I’m exhausted. You see,

saints are only human.

* * *

There once was a princess with long, flowing hair,

lovely, and also quite scholarly.

But she was beheaded—a messy affair—

for refusing to take vows of matrimony.

In case you were wond’ring, that princess was me.

He was a repulsive, ridiculous man!

If I’m slightly resentful, I think you’ll agree,

saints are only human.

* * *

About this young Joan I’ve some sympathy,

but if I forgot her, reneged on the plan,

she’ll learn the hard way: There’s no guarantee.

* * *

Saints are only human.

Joan

The journey to Chinon—eleven

days and nights—was long and hard. I

had always to be on my guard,

for not only was I in the

company of men who were not

of my blood, but the rivers were

high, in spring flood, and we traveled

through countryside the English

controlled. But I was comforted,

consoled, by the voices of my

saints. My male escorts showed constraint

and never once approached me with

impure innuendos or dis-

honorable intentions. My

accusers often mention this

as proof that I’m a witch, a wicked

necromancer. They say the only

way they can explain why healthy

men remained aloof to what is

vital to their sex was I had

practiced conjuring to produce

unnatural effects. They insist

that I had cast a spell; they insist

my voices come from Hell. They insist

I am a zealot of the black

demonic arts. They insist on

evil everywhere but in the

darkness of their hearts.

T night, Jeanne slept beside Jean de Metz and myself, fully dressed and armed. I was young then; nevertheless I never felt towards her any desire: I should never have dared to molest her, because of the great goodness which I saw in her.

* * *

Bertrand de Poulengey, squire

Trial of Nullification

Lust

I was a snake

that would not strike,

a fawning tiger,

a blunted pike,

confused and

undirected.

* * *

I was hunger,

agitated,

always wanting,

never sated,

asking but neglected.

* * *

A fire

unlit,

ale

not drunk,

a ripened bud

that grew

then shrunk,

a belfry unerected.

She was ice.

She was flame.

She was goodness.

She was my shame,

iniquity

reflected.

Joan

Before we set out on our expedition,

I made another change. It is

the accepted tradition for

young women to arrange their hair

in long and flowing tresses. This

well-established custom expresses

they are of age and available

for marriage, and is a subtle

declaration to the opposite

sex. But I have never felt compelled

to do what everyone expects.

I took up a pair of shears. My

hair is now an easy length, cut

just below my ears.

ID you wish to be a man?”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

Her Hair

I was

a flag,

a waving

splendor;

I was

a sign

to each

contender,

as full

of hope

as morning.

* * *

I am a wonder. I am ease.

I’m an avowal: I do what I

please. A fearless day aborning.

* * *

I was

encour-

agement.

I was

allure.

I was

a melody

flowing,

pure,

appealing, and

adorning.

* * *

I am a helmet on a strange head.

I am a

word that won’t be said,

a triumph, and a warning.

Joan

From the town of Fierbois, I relayed

my intention to see the dauphin,

a single day’s ride from where he

held court. My saints had supported

our long expedition, and while

we awaited the dauphin’s permission

to enter Chinon, I rested

and prayed, giving thanks to my voices

that we’d not been delayed by the

English or outlaws the war had

created. I was impatient

but also elated, for soon

I would kneel before the chosen

king of France, nevermore to tend

my father’s bleating sheep nor weed

the tender plants in my mother’s

kitchen plot. I welcomed who I

was and left behind who I was

not. The chapel at Fierbois was built

of stone and wood, and I

attended Mass there as often as

I could, finding happiness and

strength as I knelt before its altar.

Never once did I falter or doubt

I would succeed. My saints—they would

sustain me and give me everything

I need.

AVE you been to Sainte Catherine de Fierbois?”

Joan: “Yes and I heard there three Masses in one day.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Altar at Sainte Catherine De Fierbois

For hundreds of years, I’ve attended prayers of peasants and nobility, their earthly cares, their hopes, their needs, their gravest sins, so many secrets that it begins to encumber me. Stained with salt of countless tears for hundreds of years, I’m burdened by the solemn pleas, the quivering voices, the bruisèd knees of desperate, suffering penitents. They have repeated the same sentiments, intoned the same vows, or so it appears, for hundreds of years. The secrets I know, I keep interred; unforgivable sin and damning word are buried with other mysteries, swords left by knights to calm and please a vengeful god who saw their sins. Oh, the secrets I know are crushing me. But she was different from the rest. She asked for nothing, no fervent request. I was both purified and awed when, in emptiness, she offered herself to God and, baptized in her ecstasy, I surrendered and let go of the secrets I know.

Joan

To lift the siege at Orléans

was my initial charge. Henry

had the town surrounded, his army

large and well-supplied. The citizens

were starving but would not be

occupied by an invading foreign

power and so were forced to cower

in their homes like sparrows in a

storm when English arrows rained,

unable to maintain their lives

without the fear of death. The English

only had to hold their breath for

the town to fall. Saint Margaret and

Saint Catherine said that Orléans

must not be lost. I had to lift

the siege, whatever it might cost.

But first I had to gain the dauphin’s

confidence. For that I would rely

upon my holy saints and my

own intelligence. Word of our

mission traveled faster than we.

News had spread of the prophecy,

and when we rode into Chinon,

the narrow streets were crowded. I,

Joan, a peasant, a girl, was being

celebrated, lauded by the

townsfolk who were shouting, reaching

out to touch my arm or leg and

begging me to deliver France from

its English enemies. Was it so

wrong of me to feel pleased to

hear them calling out “The Maid!” as

our small cavalcade made its way

through the throng? Wrong of me to take

pride in how far I had come? Sinful

to take pleasure in the sweet hum of

hope that filled the air? Everywhere

I looked—faces smiling, laughing,

cheering! Cheering in a time of

misery and war! I loved these

people, the faithful poor. But we were

nearing the castle, the residence

of Charles, the gentle dauphin

and rightful king. I had never

seen anything so majestic

or so grand. Its towers and its

battlements fanned out on the very

top of the hill that overlooked

the town, like a protective helmet

or a shining, royal crown. My

voices whispered I would soon stand

on its parqueted and polished floors;

but they did not warn me of the

darkness lurking in its corridors.

FTER dinner, I went to the King, who was at the Castle. When I went to the room where he was I recognized him among many others by the counsel of my Voice, which revealed him to me. I told him I wished to go and make war on the English.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

The Castle at Chinon

Only

a child trapped

in the thrall of palace

rooms that wind and sprawl—each

hung with gaudy tapestries whose func-

tion is to warm and please the noble folk

when winter’s squall explodes against the

tower wall and muffles the pathetic call of

courtiers begging on their knees—only a

child could not attend the pleading waul,

the pain, the misery, the pall, that radiate

and rise from these: the blood spills and

the treacheries that fester in these lurid

halls—only a child. Where kings reside,

the sleeping dust on gilded frames knows

not to trust anything a king might say. A

promise that he makes today, though

he proclaims it with robust sincerity, is

worthless. Just and wise men know that

greed and lust, deceit and treason, often

play where kings reside a game in which

the drag and thrust of power that is won

and lost leaves innocence to die, decay. It

is a virtue to betray where kings reside.

Joan

When finally I saw Charles—

after two days of waiting,

worrying, wondering, anticipating—

they tried to deceive me. His male

advisors did not believe me

and so they put him in disguise

and introduced another as

he. The look on their faces! The shock

and surprise when they saw that I

was not so easily misled.

How their jaws dropped when I smiled

and said, “But this man is false, a

giddy pretender.” And in the

splendor of the court went directly

to Charles and gave him my knee.

My voices told me it was he. I

then described for him my vision,

my saints, my voices, and my mission

to lift the siege at Orléans.

We went into a private room,

and there in the solemn and imposing

gloom, I gave my king a sign that

everything I’d said was true. I

told him something that only he

knew—the content of his secret prayers.

WAS at the Castle of the town of Chinon when Jeanne arrived there, and I saw her when she presented herself before the King’s Majesty with great lowliness and simplicity; a poor little shepherdess! I heard her say these words: “Most noble Lord Dauphin, I am come and am sent to you from God to give succor to the kingdom and to you.�

�

* * *

Sieur de Gaucort

Trial of Nullification

Charles VII

What an embarrassment to me—

this peasant wench dressed in men’s clothes!

To come before me! Royalty!

In tunic! Doublet! And in hose!

* * *

A reprehensible affront that goes

against all laws of propriety!

She says she is unschooled. It shows!

What an embarrassment to me!

* * *

To all the aristocracy!

She should be whipped! But then suppose . . .

suppose that her hyperbole—

this peasant wench dressed in men’s clothes—

* * *

suppose she speaks the truth. A Christian knows

that God’s work is a mystery;

she may well be the one He chose.

To come before me, royalty,

* * *

takes unusual bravery.

Can she defeat our English foes,

deliver France its victory,

in tunic, doublet, and in hose?

My noble courtiers oppose

her and her tale of prophecy.

Yet she was able to disclose

words I’d said in secrecy.

What an embarrassment!

Joan

Before I could set upon my

mission to roust the English, save

Orléans, and lift the siege, Charles,

the dauphin, my king, and my liege,

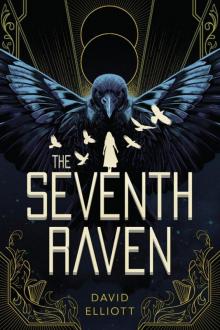

The Seventh Raven

The Seventh Raven Voices

Voices Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie

Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie Fluke

Fluke