- Home

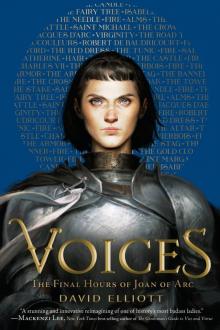

- David Elliott

Voices Page 3

Voices Read online

Page 3

I fulfilled my duty to protect my daughter.

I taught her to keep her eye

* * *

turned inward, to reject temptation, to avoid the eye

of the serpent, unlike Eve, who traded life

in the Garden to know evil. Woman is the daughter

of sin, and if unchecked, the ruination of a good man,

the humiliation and sorrow of a loving father,

an embarrassment to her brothers and sons.

* * *

My wife has given me three fine sons.

Their backs are strong and straight; their eyes

are clear. They will honor me, their father,

when I take my place on the great circle of life.

I am a farmer, but am richer than a nobleman

whose wife’s womb yields only daughters.

* * *

And as for Joan, my eldest daughter,

she was stronger in temperament than my sons,

as grave in her demeanor as a virtuous man.

But I sometimes saw a spark in her eye:

the spark of ambition. It would ruin her life

and the name and reputation of her father.

* * *

Obedient, chaste, respectful to her mother and father,

in almost every way, she was the perfect daughter,

working more in a week than many girls do in a life-

time. But she would never bear me grandsons.

I knew this as sure as I knew that oxeye

daisies thrive over the grave of an honest man.

* * *

Daughter, I said to her. Listen to your father.

Man is your light. Find a husband. Give him sons.

Life wants nothing from you. Remove that spark from your eye!

Joan

The morning sky is gray, and a

crowd begins to form. The townsfolk

are aroused today. Buzzing like

a swarm of bees, they have come to

watch me die. Some of them are ill

at ease, but not as ill at ease

as I. Reluctant to remember,

reluctant to forget, I am

defiant in my triumph but

taunted with regret. I think

of all I have experienced,

and all that I have not, every-

thing I kept in darkness and the

suffering that it brought. I did not

tell my father that I would never

wed. I did not tell myself that

I had other desires instead,

desires that I fought against,

desires I could not name, desires

that spoke an unknown tongue, desires

that lit a flame. Even now when

at the end, with nothing left to

lose, I cannot identify

what I could never choose.

ROM the first time I heard my Voices, I dedicated my virginity for so long as it should please God; and I was then about thirteen years of age.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

Virginity

I am a bed

forever made.

I am a fortress,

a stockade,

a desert and

a garden.

* * *

I am a chamber,

ever locked.

I am a weapon,

never cocked.

A sentence and

a pardon.

* * *

A stone,

a field

unsown,

unplowed,

a vow,

a habit,

gown

and shroud,

I soften and

I harden.

* * *

I am

an absence,

a tranquil

O.

I am all

she will

never know,

* * *

her prisoner

and her warden.

Joan

The next three years I often spent

alone. I did my chores as always

but the angels had shown me that

my life was not what I thought that

it would be. I was sometimes then

in a state of ecstasy, marred

only by the anxiety

of knowing what I was called to

do. But as time passed, my confidence

slowly grew until the day my

saints instructed me to leave my

Domrémy for the nearby town

of Vaucouleurs, where Robert de

Baudricourt, my voices said, would

get me to Chinon and the unanointed

king. I left my family, my

friends, everything I had loved or

known. I did not say goodbye;

they would not have let me leave. I

was a girl. I was alone. There

was no other choice but to deceive.

HE Voice said to me: “. . . Go, raise the siege which is being made before the city of Orléans. Go!” it added, “to Robert de Baudricourt” . . . I went to my uncle [Durand Laxart] and said that I wished to stay with him for a time. I remained there eight days. I said to him, “I must go to Vaucouleurs.”

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

The Road to Vaucouleurs

I do not know where I begin.

And where I end I do not

know. I do not move but still

I bend. Was I a traitor or her

friend? What does her destiny

portend? I do not know.

* * *

Upon my back I felt her weight.

She walked alone upon my back.

She passed the fields, the mound-

ed stacks, the surest step I’ve ever

known and yet a girl not fully

grown upon my back.

* * *

I took her there. To her longed-

for destination I took her.

There was no choice. I took

her where she would begin her

new vocation. To her glory

and damnation, I took her there.

* * *

I do not know where I begin.

And where I end I do not know.

I do not move but still I bend.

Was I a traitor or her friend?

What does her destiny por-

tend? I do not know.

Joan

I never once looked back.

From that bright morning to this

black day, there’s been for me

no other way. In the fearless song

of every serenading bird,

I hear one pure and piercing anthem:

Onward!

HEN I arrived, I recognized Robert de Baudricourt, although I had never seen him. I knew him, thanks to my Voice, which made me recognize him. I said to Robert, “I must go into France!” [France was equivalent to wherever Charles was.] Twice Robert refused to hear me, and repulsed me. The third time, he received me, and furnished me with men.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

Robert De Baudricourt

It is a testimony to my iron will

that Vaucouleurs has never lost its way.

I have kept the English army out

because I am a man, the kind of man

who brooks no fools. I have no time

for prophets, seers, dupes who have a dream

* * *

and think it leads to truth. What is a dream

but a storehouse of a day’s events? And who will

say it’s more is he who wastes my time.

Or so I used to say, the narrow way

I used to think. Now I’m like a man

evicted from his home, who’s been turned out

* * *

from the com

fort of his own beliefs, out-

done and conquered by a girl who dreamed

that she and she alone would do what no man

has done, who came to me and said, “I will

expel from France all those who break away

from Charles, the rightful king, and the time

* * *

has come for you to help me in my quest.” But time

was short, she said. She insisted she must go out

of Vaucouleurs, that I must help her find her way

to Charles, that I must help fulfill her dream,

that I, Robert, was subject to her will,

which was the holy will of God. What man

* * *

would dare to speak to me like this? What man

would have such insolence? Time after time

she came to me. A girl! But the power of her will

was stronger than my own. Twice, I threw her out

but dogged as a sharp, recurrent dream,

she reappeared, standing in my doorway

* * *

like a boulder, in her off-putting way,

her shoulders squared, as bold as any man

I’ve ever known. Now I often daydream

about that uncanny girl. Though my time

in Vaucouleurs with her was brief, throughout

my life, I’ve not met another like her. I never will.

* * *

In the end, I was a man in a dream, her dream,

and afflicted with the sentiment that my time was running out.

“Take what you need,” I said. “I will not stand in your way.”

Joan

I endured the scorn of Baudricourt,

his contempt, his mocking laughter, and

the rank hostility of all

the men who came after. Though assailed

by their derision, I prevailed.

My vision never faltered. I

stood in front of them unafraid,

unaltered, until gradually

their privilege and their power

began to fade and weaken like

a flower in a time of drought.

If ever I was plagued by

anxiety or doubt, I put it

aside and fought arrogance with

arrogance and pride with

burnished pride.

Fire

I thrill I thrill I thrill my darling

I thrill I thrill I thrill

I burn I burn I burn my darling

I burn I burn I burn

I yearn I yearn I yearn my darling

I yearn I yearn I yearn

Joan

“Take what you need,” he said. I stood

before him in my red dress and

made a list. I would need men to

give assistance and escort me,

men who would comport themselves

with honor, men I could trust, men

who could control their lust. For when

we traveled to Chinon, I would

have no female chaperone to

shield me from these knights and squires,

who might publicly admire my

valor and my spirit but privately

would prove themselves by trying to

get near it. The road, I knew, was

treacherous, our enemies

surrounding us until we crossed

the river Loire, our destination

far away. So I determined,

come what may, that I would not depart

unarmed. I would meet the future

king unharmed, untouched by guide or

English horde. My heart was pounding in

my side when I asked him for his sword.

ROM Vaucouleurs, I departed . . . armed with a sword given me by Robert de Baudricourt, but without other arms.

* * *

Joan

Trial of Condemnation

The Sword

Joan

But I knew a sword was not enough.

I would not meet my king in a

rough red dress, a signal that I

was less than I knew myself to

be. My blessed saints had given me

the liberty that I had always

craved, a freedom I had not been

brave enough to take. Now, at last,

I resolved that I would shake off

the russet shell that had defined

me, locked in, constrained, and

undermined me. The young dauphin

would find the Maid as she was truly

meant to be. Though I knew I would

be subject to every kind of

ridicule and personal attack,

I took a breath and crossed a line.

There would be no going back.

HEN Jeannette was at Vaucouleurs, I saw her dressed in a red dress, poor and worn.

* * *

Jean de Metz, squire

Trial of Nullification

The Red Dress

I can’t forget that day

in Vaucouleurs. She tore me

from her body as if I’d stained

her skin, and left me like a

corpse on the cold, indurate floor.

She’d worn me every day—no

choice—but at her very core she bore

me an antipathy as sharp as any pin. No,

I won’t forget that day in Vaucouleurs—

the way she turned and walked so boldly

out the door, leaving me to wonder, alone

with my chagrin, as lifeless as a corpse on a cold,

indurate floor. I’d never heard her laugh like that

before, as if she’d been relieved of agony that

twisted deep within. On that strange and fateful day

in Vaucouleurs, it was in that very room she knelt

and swore to never wear a woman’s shift again.

Once she left me on that cold, indurate floor, she disap-

peared; I never saw her more. What was my transgression?

What my sin? Forgotten in the town of Vaucouleurs,

abandoned like a corpse on a cold, indurate floor.

Joan

The dress was made of homespun that

I myself had cut and sewn, yet

it pressed against my shoulders as

cumbersome as stone. There were times

I had the strange idea it longed

to pull me down. But I would have

felt the same in any dress or

gown, even those constructed of

rich brocades and lace. In vestments

other women wear with ease, I

felt false and out of place. But that

day in Vaucouleurs I knew there

was attire that suited me much

better, clothing in which I saw

myself solid and unfettered,

and in which I would no longer

play the mute in a dishonorable

charade. So I stepped out of the

red dress and left behind the

masquerade, the costume, and the

mask. And with it Joan the girl and

daughter, and her domestic tasks.

ASKED her when she wished to start. “Sooner at once than tomorrow, and sooner tomorrow than later,” she said. I asked her also if she could make this journey dressed as she was. She replied she would willingly take a man’s dress.

* * *

Jean de Metz, squire

Trial of Nullification

The Tunic

Joan

I have led men into the nether-

world of battle. I have contended

to the tumult and the rattle

of besmirched and bloodied swords. I

have rallied screaming soldiers toward

their death, stepped over fallen warriors

to the rasp of their last breath. But

the boldest action I have

&n

bsp; taken was in that domestic

dressing room. It led directly

to myself, and directly to

my doom. How often did they ask

me why I would not wear a dress.

How they frequently berated

me and urged me to confess that

to put on the clothes of men was

a foul abomination. They

said it was a mortal sin and

even promised me salvation

from the smoke and scorching fire if

I would just recant and put on

women’s attire, the way, they said,

that God Himself intended. They

said my tunic and my doublet

derided and offended all

that to Him was sacred. And in

a moment of great weakness, I

recanted and relented. They

offered me a dress; I nodded and

consented and said that I would

wear it. But once back in my tower

cell, I knew I could not bear it—

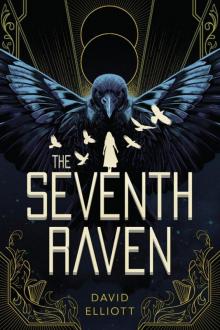

The Seventh Raven

The Seventh Raven Voices

Voices Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie

Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie Fluke

Fluke