- Home

- David Elliott

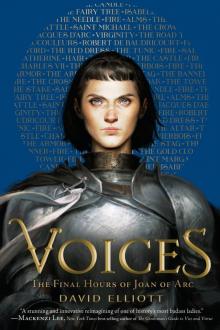

Voices Page 6

Voices Read online

Page 6

should have no fear. I was sent here

to protect him. Thanks to my saints,

the weaker counsel did not infect

him. In the budding month of June

we began our appointed journey:

the king, his court, my army, and

at the head of the procession,

me, mounted on my charger. He

was larger than other horses

and in possession of a wild

and fearless temperament. That we

belonged together was evident

from my first time on his back, me

commanding in my armor, him,

proud and shining black.

HO had given you this horse?”

Joan: “My King, or his people, from the King’s money.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Warhorse

Not for me the slow life of the field and the plow

and the farm and the farmer’s dull monotone

as he harvests and rakes while the sweat of his brow

drops to the soil like the seeds he has sown.

* * *

I was bred for the babel; I was bred for the how

and the why of the fight and the withering groan.

Not for me the slow life of the field and the plow

and the farm and the farmer’s dull monotone.

* * *

I was bred for the knight and his bellicose vow

to enter the fray. Muscled loin, strong of bone,

firm of heart, wild of eye. Who would dare disavow

the bond of my breeding, the courage I’ve shown?

* * *

Not for me the slow life of the field and the plow.

* * *

And she was like me and so we were one.

We were the wind, untamed, unafraid

of the enemy’s grit; we were fierce renegades,

unflagging, unyielding, until we had done

* * *

what we set out to do. There was none

who could check us; though she was a maid,

she was like me and so we were one

when we were the wind, untamed, unafraid.

* * *

Many a knight had been cowed and outdone

by my spirit, left broken, unseated, unmade.

But she understood. Unbridled blood runs

molten and wild, unrestrained, unsurveyed.

* * *

And she was like me and so we were one.

Joan

The shuffling of the soldiers’ feet

raised a tremendous cloud of dust

that could be seen from a great distance.

It gave the captains of the towns

the time to know if they should continue

their resistance or come to a

more peaceable decision. Would

they recognize their rightful king

and enjoy his supervision?

Or would they fight? One after another

they stepped out of English darkness

and came back to the French light.

Cravant, Bonny, Lavau, all welcomed

us, and Saint-Fargeau fell without

a fuss, not a single arrow

in the air. And so it was with

Coulanges, Brinon, Saint-Florentin,

Auxerre. I always rode ahead

to let them know the Maid was at

their door, foolish to oppose, at

their great peril to ignore. And

in the wind, the banner Charles

made for me—white, depicting

angels, and golden fleur-de-lis.

HICH did you care for most, your banner or your sword?”

Joan: “Better, forty times better, my banner than my sword.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Banner

Above her head the sparrows huddle in the trees. Above her

head they listen with increasing dread. The phantoms

of her enemies are wailing in the morning

breeze above her head. Above her head

I scream a terrifying prayer. Above her head,

a warning from the newly dead to not resist for who

would dare to fight the angels singing there above her head?

Joan

Reims, too, was in English hands but,

before a sword had left its sheath,

it gave in to my demands. Not a

halberd thrown or a single word

of coarse debate. The residents

opened wide their city’s gates as

the frightened English soldiers fled.

All of Reims bowed its head when Charles

rode through its cobbled streets. Word of

my military feats had also

reached their ears. I saw their suffering

faces wet with tears of unchecked joy

and raw relief. But to my eventual

sorrow and certain grief, in the

young king’s retinue there were those

who, because I was not a man

but in men’s clothes, thought I was a

blasphemer and a troublesome

disgrace. They resented my place

in the royal court and worked behind

my back to thwart my influence

with the king. I did nothing to

stop their gossip, their intimations,

or their tricks. My place was with my

king. I did not stoop to politics.

Instead, I attended to the

coronation. There is no apt

description nor sufficient explanation

for what occurred in the cathedral

there. The very air felt sanctified.

I was filled with joy and pride as

Charles VII, king of France, was

coronated and anointed.

I stood beside him—not behind.

And appointed in my finest

armor, I reminded myself

that I, the daughter of a lowly

farmer, had brought this holy day about.

I still can hear the people shout . . .

Or is that the throng in front of

me calling me a slut and witch,

their faces warped in anger, their

din a frenzied pitch?

Fire

I’m near I’m near I’m near my darling

I’m near I’m near I’m near

I roar I roar I roar my darling

I roar I roar I roar

I soar I soar I soar my darling

I soar I soar I soar

I will I will I will my darling

I il l I will I w ll

thr I ill I thr my d rl ng

I thr I ri I

Joan

But my king could save me still. If

he has the will, he could ransom

me. The price would be handsome, but

he could set me free. Everything

I did for France—he won’t forget.

Charles is God’s chosen king:

I know he’ll save me yet.

Charles VII

What an embarrassment to me—

this peasant wench dressed in men’s clothes!

To appear before me! Royalty!

In tunic! Doublet! And in hose!

* * *

A reprehensible affront that goes

against all laws of propriety!

She says she is unschooled. It shows!

What an embarrassment to me!

Joan

There was so much more to do after

the victory at Reims. Henry

still held a large expanse of French

land, and Paris, too, was in his

grip. Though my voices did not tell

me to, with the approval and

companionship of my men and

the king, I set my sights on that

great city. There wou

ld be no mercy

and no solace, no pity for

the false French who there resisted,

whose loyalties had been so grossly

twisted that they would dare defy

me. I needed Charles to stand

beside me, but for seven long

weeks he reveled in his coronation

and stopped at every town that

welcomed him for drink and celebration.

By the time we reached the city

gates, our fates were set and firmly

sealed, for the English had prepared

themselves and concealed weapons and

ammunition around and on

the city walls—stones, crossbows,

cannonballs ready to be fired.

My men were eager and inspired,

their courage hot and high, but an

archer caught me in the thigh, and

the aide who held my banner also

fell, and with it our offense. My

army lost its confidence. When

I was carried from the field, Charles

ordered a withdrawal and my men

were forced to yield.

ID you not say before Paris, ‘Surrender this town by the order of Jesus’?”

Joan: “No, but I said, ‘Surrender it to the King of France.’”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Crossbow

Joan

The king seemed to retreat from me

after my defeat at Paris.

It was the ferrous tongues of my

detractors that caused this change in

his opinion. Among his minions

at the royal court, bad actors

undermined the king’s support by

telling him my character and

comportment would taint his

reputation as a good and

Christian king. I was, they said, an

aberration. A girl who dressed

and acted like a man was a

sinful, monstrous thing he should no

longer tolerate. I’d served my

usefulness, they said. He should remain

aloof. They said I’d been abandoned

by my saints, and Paris was the

proof. My saints, too, which had always

come to me unbidden, remained

distant and silent, hidden unless

I called on them to ask for their

advice. I did this once or sometimes

twice a day. They never turned away

from me but they no longer charged

me with specific tasks as they

had at Orléans and Reims, and

I began to ask myself if

I’d fulfilled my duty to

my king and to my country, France.

But how could I return to

Domrémy, its drudging tasks and

dreary obligations? The military

life had its deprivations, but

it was what I loved and wanted.

I would not be shunted back to

the barn and field, not allow my

current life to be repealed by

the domestic rut I hated,

to be betrothed, wed and mated,

like all the girls I used to know.

* * *

A kind of fearful loneliness

began to germinate and grow.

I felt abandoned, almost ill,

and shaken and so I became

bolder still and started to take

risks I ought not to have taken.

At Compiègne, I rode out among

the English forces—their angry peasant

footmen, their knights on armored horses—

in a cloak of shining gold. I

told myself that once they behold

the Maid of Orléans, fierce and

gleaming in her splendor, they would,

like all the other towns, come to

their senses and surrender. But

the English there were not as

easily impressed as I had

thought. A common soldier grabbed the

cloak. He pulled me from my horse, and

I was captured, caught not only

by a footman who had his eye

on me, but also by my recklessness

and the sin of vanity. I

loved that cloak; it made me feel

invincible and like a royal

son. How confusing that I love

it still, though through it I have been

undone.

AD not your Voices ever told you that you would be taken?”

Joan: “Yes, many times and nearly every day. And I asked of my Voices that, when I should be taken, I might die soon, without long suffering in prison: and they said to me: ‘Be resigned to all—that it must be.’ But they did not tell me the time; and if I had known it, I should not have gone. Often I asked to know the hour: they never told me.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Gold Cloak

We were as splendid

as the noonday sun,

and in our glory would

blind our staring enemy.

But all stars fall when their

time to shine is done. Our fame

was known to everyone. Taken

with our own mythology, as bright

and splendid as the noonday sun, we

fought our battles. One by one by one,

singing, shouting, “Victory!” But all stars

fall. When their time to shine is done they

fade and disappear. None can escape that dull

and awful certainty, though once they shined as

splendid as the noonday sun. What we’d begun

ended. Now it’s only history, like stars that fall when

their time to shine is done. She wasn’t able to outrun her

fate. Each of us has a destiny as sure and splendid as the

noonday sun. But all stars fall when their time to shine is

d o n e .

Joan

I was taken on the twenty-

third of May, and the next day they

brought me to Beaulieu les Fontaines.

But when, in July, I nearly

broke free, they improved their

weak security and removed me

to the tower at Beauvoir. It

was a foul place; the air was sour

but the windows lacked bars: My cell

was seven stories high. Was it my

intention, when I jumped, to enter

Paradise and die? Or did I

believe my blessèd saints would

teach me how to fly?

AVE you never done anything against their [her Voices’] command and will?”

Joan: “All that I could and knew how to do I have done and accomplished to the best of my power. As to the matter of the fall [leap] at Beauvoir, I did it against their command; but I could not control myself. When my Voices saw my need, and that I neither knew how nor was able to control myself, they saved my life and kept me from killing myself.”

* * *

Trial of Condemnation

The Tower

In

another life,

I might have been

a crimson dress made

to inhibit and oppress, worn

by women, cut and sewn. Now my

skin is mortared stone made by men for

war and strife. In another life

she might have been a man,

no more an anomaly than

any other natural man. Not

a danger. Not a threat. Then

she and I would not have met.

She might have been a far-

mer’s wife in another life.

Joan

I still don’t understand why I

did not die the afternoon I

leapt. D

o my saints think this a better

way? To be kept like a beast in

a darkened cell? To never see

the light of day? To be consumed

by smoke and choking fire? Did I

not do well in what they asked of

me? In what way did I offend?

Does my death require something that

I cannot comprehend? Or might

Saint Margaret save me still? The sun

is nearly at its peak, but she

has asked me to have faith. And so

I will.

Saint Margaret

Faith isn’t for the faint of heart.

Both courage and naïveté

are required. To grasp its art,

you must look the other way

when all the omens seem to say

you will not get what you desire,

so, though it may be a cliché,

I put my faith in fire.

* * *

Flames are devoted. Once they start

their urgent work—some call it play—

you may depend, they won’t depart

until they’ve kept their word. Their way

is not to waver; they obey

a law more natural. As they grow higher

they will not falter or betray.

So put your faith in fire.

* * *

Fire will scorch and singe and smart;

she cannot keep its pain at bay.

It will destroy her, then depart,

leaving ashes, cold and gray.

Though she may beg and plead and pray,

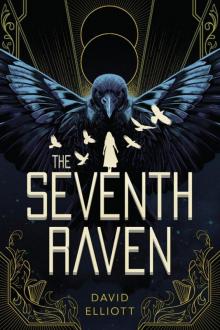

The Seventh Raven

The Seventh Raven Voices

Voices Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie

Private Eye 2 - Blue Movie Fluke

Fluke